Is the mood shifting against meat?

Robert Blood, founder of SIGWATCH, which monitors NGO activities, believes there has been a sea change in attitude about meat

The revelation that one in three British people is either trying to reduce their consumption of meat or cut it out of their diet entirely is merely another sign that meat is set to be the next plastic, according to Robert Blood, founder of SIGWATCH.

The findings, which were contained in a survey undertaken on behalf of grocery chain Waitrose, also revealed that one in eight people – or 12.5 per cent – now identify as vegetarian or vegan.

Only two years ago, a survey by the Vegan Society suggested that just 3.25 per cent of Britain’s population were vegetarian or vegan. And more recently the Committee on Climate Change warned that Britons must eat less red meat if the UK is to meet its targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The Government watchdog has calculated that ‘enteric fermentation’ in Britain’s sheep and cattle, which causes them to fart and burp, produces the equivalent of 23 million tonnes of CO2 a year.

‘The signs keep popping up,’ says Blood, who also points to workspace provider WeWork banning meat from its cafeterias and company events and announcing that it would no longer allow staff to expense meals containing meat. ‘Everything tells us that it is coming. But is it a slow burn – a generational change – or is it something that is going to happen like a tipping point [when public sentiment will switch against meat]?

‘In certain countries, I feel it is already reaching that tipping point. But when I say to people 12 to 24 months, they are incredulous. And even I start to wonder if that is too soon,’ he adds.

‘There is a temptation to stretch the prediction, so that it feels more reasonable, but actually I feel that it is happening more quickly than that.’

His concerns are prompted by a rise in activist campaigning concerned with the environmental impact of meat within the last four years, which has gathered pace over the past 12 months. SIGWATCH analysis suggests that there is four times as much NGO campaigning linked to meat consumption today compared to five years ago.

‘One thing we have learned from NGOs is that they are quite commercial in the way that they operate. They don’t pursue campaigns for the good of their health, but presumably because they work and make an impact,’ he adds.

‘NGOs might float balloons, but they won’t pursue them for very long if there is no support. When they get behind issues like plastic, it is because they are hearing the dog whistles even if no one else is. They sense it is beginning to bite.’

One thing we have learned from NGOs is that they are quite commercial in the way that they operate.

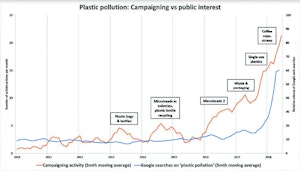

SIGWATCH has been tracking NGO campaigning for the past 20 years, and currently monitors more than 9,000 organisations. ‘We can see how issues ebb and flow or, in some cases, go into a hockey stick motion – albeit a bit drawn out. When we apply that analysis to issues that have reached tipping point, there is a clear feedback mechanism going on,’ explains Blood.

‘In other words, campaigning activity rises in anticipation of social awareness. What is interesting is how much activity appears to anticipate it – sometimes 12 to 18 to 24 months in advance. It is something we have not been able to explain: why do NGOs significantly increase the volume of their campaigning when apparently nobody is listening? And then they do listen.’

He adds: ‘A rise in NGO campaigning anticipates a later rise in public concern, which in turn forces the issue onto the political agenda and demands a response from governments and business.’

The consultancy also monitors Google web searches on issues, and has noted that global searches for the topic veganism picked up about 18 months after NGOs started to develop campaigns focusing on the impact of intensive livestock-supporting agriculture on biodiversity.

‘We are trying to find good media data: we think there is a media curve that sits somewhere between the campaigning curve and the public awareness curve – media awareness builds social awareness – and media awareness comes from campaigning.’

At the end of 2017, four years after NGOs first unveiled a series of micro campaigns targeted at plastic, such as packaging, plastic bottle manufacture and recycling and microbeads in toiletries, there was a five-fold increase in the volume of Google searches for plastic pollution.

‘The NGO campaigning does seem to work. We’ve shown it for plastics and for fracking. We have looked at different issues like this and found a similar pattern, which allows us to theorise, particularly if we see certain events happening in the campaigning space, such as major groups like Greenpeace and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) pressing the non-meat-eating cause,’ says Blood.

‘This means they are comfortable and believe that their publics are comfortable hearing that message.’

Over the past year, Greenpeace has launched anti-meat and animal farming campaigns in France, Germany, Russia, Switzerland, Austria and New Zealand.

Similarly, the WWF has called for people to cut back on meat consumption while engaging with the food industry to reduce the environmental impact of meat production.

He adds: ‘The fact that they [NGOs] are putting more resources behind this is not simply that they have spotted a deep truth. It is a moment whose time has come. It is a behaviour change. If food businesses and restaurants see more vegetarian customers, they will put on more interesting and compelling menus with vegetarian options. It becomes self-sustaining.

‘I suspect what we are really talking about is flexitarianism – avoiding meat on some days of the week – and that it is going mainstream. You can have a very enjoyable meal without any meat, and there is no penalty in avoiding meat but rather a virtue.

‘We think the justification will be the environmental case – which is where the virtue will come in. Some people will argue it is about health, others that it is about animal welfare. Both categories have always existed, but they have had very little impact on the population. The difference now is mainstreaming vegetarianism, which requires justifying eating meat rather than not eating it.’

The fact that NGOs are putting more resources behind this is not simply that they have spotted a deep truth; it is a moment whose time has come

The danger posed by such a rapid escalation is that it can be dismissed as a fad, explains Blood, who claims that the meat industry has already taken such an approach. ‘The future is frantically signalling at us,’ he adds. ‘We can either pay attention or ignore it. It looks like it is going to happen, and it looks like it is going to happen faster than we were expecting. It has gained momentum.’

The tipping point for the plastic issue was Sir David Attenborough’s Blue Planet II series, which explored the planet’s oceans and revealed the environmental impact of plastic. Blood believes that meat could be ‘strategically as significant as plastic’.

He adds: ‘It is a bit like smoking. Pressure on smoking has been growing for some time, and we are now at a point where smoking is so much a minority habit that governments and businesses feel very happy in restricting smokers. ‘Obviously you can’t argue that people’s meat eating is oppressive to others in the way that smoking is. But you could argue that the environmental and climate change footprint of meat eating is a generalised bad, and therefore we should socially restrict meat eating for the good of all. Culturally, when you get to a point where meat eating must be defended, you know a tipping point may have been reached.’